Please install a more recent version of your browser.

20 January 2021

6 minutes read

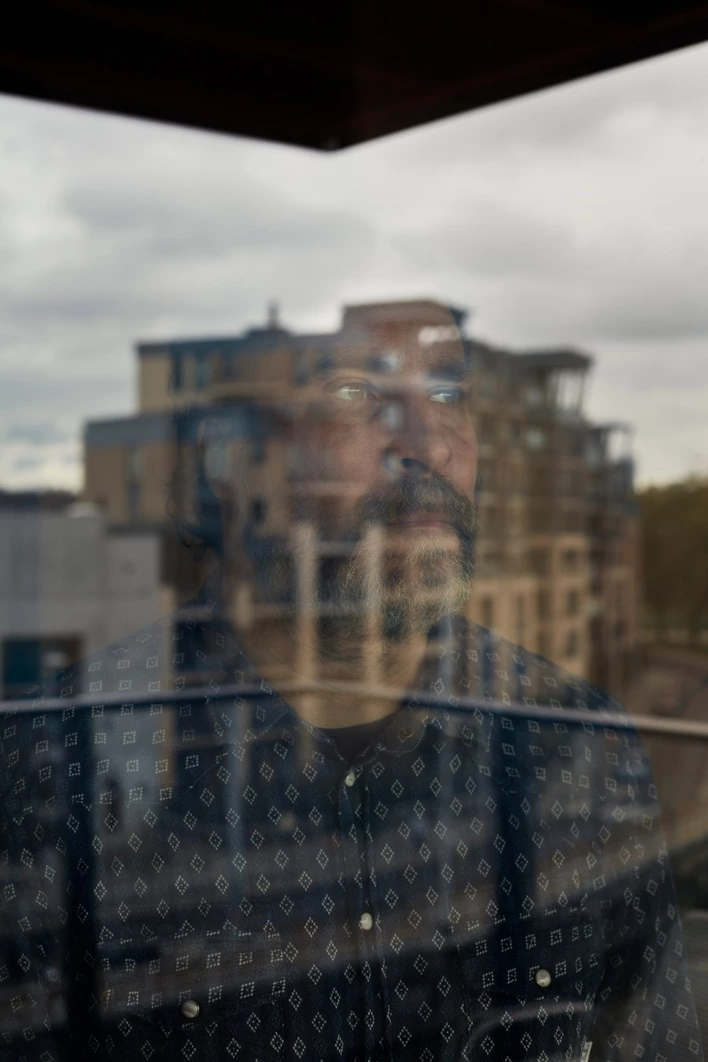

Nico is called the secret weapon of the Belgian film industry. A weapon located in the darkness of the editing room. Film has been his passion since he was sixteen. Nico Leunen studied directing and experimental film at LUCA School of Arts. There he discovered that editing suited him most. Fellow students asked him to edit their films. That’s what started the ball rolling. And it rolled all the way to Hollywood, to Ryan Gosling and Brad Pitt. Film editors rarely become famous, but Nico’s star rises with every production.

Wil je op de hoogte gehouden worden van nieuwe artikels in dit magazine? Schrijf je in op onze nieuwsbrief!

© Dennis & Did

That’s the discussion you have when you talk about success. Is it also part luck or mainly down to hard work? It’s probably a combination of the two. And you have to meet the right people, which causes chain reactions. Of course, you have to live up to it, but if you love doing it, you can.

Too big an ego is one of the major occupational risks. Most editors do have some creative blood flowing through their veins. And they apply all that creativity for others. You have to know how to deal with that. After all, many creatives want to express themselves. And that’s not what it’s about. One of the biggest mistakes you can make is thinking that the movie is yours at one point or another.

That’s a challenge. But limitations can actually lead to very creative solutions. For example, you can play with the order of scenes or change the theme within a scene. A character who approaches a scene angrily, but makes up for it, can also make you angry in that scene. You can only do it if you look beyond the available material, at the material that might be there. You look a dimension further, and sometimes you find solutions that are not that obvious.

You get under their skin. To understand emotional decisions and storylines. Just like an actor, but with several characters at the same time.

You work day in, day out, in a darkroom on screens.

Whereas in some professions you are more likely to shake it off physically, it is not unusual for an editor to have to cope with a heavy psychological burden. You can call it the occupational hazard of our profession. You’re also a kind of therapist for the director at the most vulnerable point of the production. Everything has been filmed, and he can’t do any more, even if it didn’t all go as planned. So you have to deal with certain disappointments and provide perspective. That’s the therapeutic side.

© Dennis & Did

It’s our pain kick. I have run into that a couple of times. It definitely involves a risk. One of my most talented former assistants also calls it the most underrated element of our profession. I like to point it out to young people I enjoy working with. I want to offer them advice and support. Other colleagues may be less inclined to do so. But at the end of the day, I would like to measure my success by the number of successful colleagues I have been able to help grow.

Unfortunately, it has happened to me a few times. But that’s really a worst-case scenario. As a rule, it works well. Sometimes it’s a leap in the dark because you only know the director by name, although some of the best collaborations were based on just a few encounters. What’s more, I have had less pleasant experiences with directors who are widely regarded as ‘cool’.

Few people know what someone is like in the editing room.

With my working method, a director should not be afraid to be vulnerable. This is obvious to people who have worked with me more often, such as my girlfriend or Felix Van Groeningen. They, too, may reach a low point, but they also know that it will all work out. The first time, you have to build that trust.

He ended up with someone else first. But when that didn’t work, he was advised through the grapevine to ask me to help him out. I was in Hollywood, but it didn’t feel like it. It was a small movie made on a limited budget. I did the editing and stayed at his house. Of course, it took some getting used to sitting next to Ryan Gosling, who you know from the big screen. But it soon became similar to working with someone like Felix Van Groeningen. It’s the same dynamic. It did get some media attention, but it’s not like my phone was red hot right afterwards. The film did make it all the way to Cannes, putting you on the radar with a wider audience. Nevertheless, the jobs come mainly through word of mouth.

© Dennis & Did

The costumes, the décor and the photography are more visible in a production. Because a director has a certain look-and-feel in mind, he or she might choose a costume designer, for example. It doesn’t work that way in my business. At best, our work is invisible. But the way you get to the end result in the darkroom does get around.

The editing of the film Ad Astra had gotten stuck. Among other things, he had seen Beautiful Boy by Felix Van Groeningen before and after my intervention. He decided to invite me based on that. However, Brad Pitt was not the director. He was both a producer and an actor in the film. So there were other interests at stake.

At worst, they want to leave their mark. At best, they want the film to do well and make a constructive contribution. I do note, however, that the pressure from the producer is directly proportional to his or her investment. When it involves a budget of 300 million euros, you don’t mess about. In that case, the interference can be defended to a certain extent.

It’s evolving, although 95% of my work still consists of auteur films. New challenges keep me on my toes, but I will never reject auteur cinema. That’s what I grew up with, and that’s what I prefer. By the way, I prefer to use ‘auteur film’ rather than ‘arthouse’, because the latter term immediately determines a film’s final destination. As if it shouldn’t end up in a big cinema. So I’d rather talk about the source, the auteur, than the final destination, the arthouse.

© Dennis & Did

There’s a different kind of suspense. Every episode has to have that. The specific difference is that you have to end up at an exact time limit, which is less so with a movie. That’s really weird to work towards. In Derek Cianfrance’s I Know This Much Is True, I was even hired as the solution to the time pressure, as an anti-stress machine.

The idea grew out of conversations I had with Ryan Gosling when we talked about the coincidental way he had ended up with me. He suggested that I get an agent and gave me tips on choosing the right one.

An agent makes life a lot easier.

I found a new American start-up in Europe that now has the most interesting agency in Europe. They help with more than jobs, they assist you in acquiring a suitable salary and good working conditions.

In my very first conversation with my agent, I got the same question. I cited Derek Cianfrance, thinking that he has only worked with his regular editors from the very beginning. When he suddenly contacted me, it was a no-brainer for me, and it was also a fantastic collaboration. Ryan Gosling and Brad Pitt can certainly call again, but it may be that...

© Dennis & Did

Cookies saved